Creating and restoring new habitat or accidently spreading plant pests and pathogens?

This post is greater than 6 months old - links may be broken or out of date. Proceed with caution!

By Ruth Mitchell, Plant and Soil Ecologist

Plants are fundamental to our landscapes, underpin many of our rural industries and recreational activities, and are the building blocks of our habitats. However, we are experiencing an exponential increase in non-native plant pests and pathogens due to increased global trade and climate change which are causing substantial economic losses. There is growing awareness of the damage plant pests can do within the agricultural, horticultural and forestry industries. What is less commonly considered is the impact non-native plant pests and pathogens can have on the natural environment. As our native plants have not co-evolved with these pests/pathogens, the pests/pathogens can cause serious ecological damage. They can cause large scale mortality of our native plants, as seen with the non-native fungus currently killing many of our ash trees. This in turn can impact a wide variety of other species that depend on that plant species driving further losses in biodiversity.

The most effective way to limit the risk of new pests and pathogens impacting our natural environment is to stop their establishment. Most new pests and pathogens arrive in the natural environment through some sort of human aided process, such as transport in soil or on translocated plants. Habitat restoration or creation is a major activity whereby plant pests and pathogens could establish, due to the amount of machinery, soil, and/or plants that are often involved. In autumn 2021 CJS members participated in a survey run by Scotland’s Plant Health Centre and NatureScot to better understand how those involved in habitat restoration or creation view the risks posed by plant pests and pathogens and what they currently do to reduce those risks. Here we report back on some of the results.

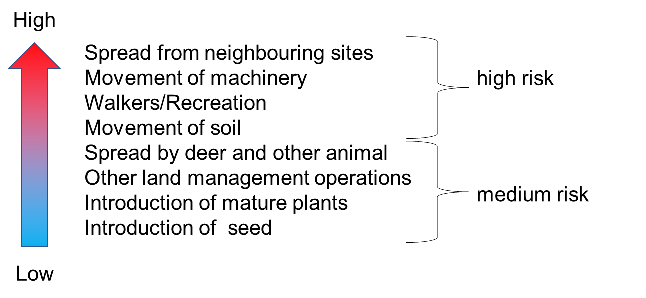

Participants assessed the likelihood of pests and pathogens establishing at sites they were involved with via 10 different routes (Figure 1). Spread from neighbouring sites was ranked highest risk whereas the introduction of seed was ranked lowest. If neighbours are perceived as the most likely source of infection of pests/pathogens rather than any activity carried out by the participants, this raises the question of how much participants are prepared to alter their own activities to reduce risk. For example, they may feel it is not worth changing their activities to reduce the risk, if the greatest risk is from their neighbours. The survey also showed that participants rank the risks of pests and pathogens establishing from mature plants and seed as similar. This is contrary to the literature which suggests that use of seed in habitat creation/restoration is considered intrinsically lower risk than translocations involving living vegetative tissue, as many (but not all) plant pathogens are not transmitted by seed.

When mature plants are moved a “biological package” is moved that contains not only the plant but also any organisms that are on that plant or in the soil surrounding the plant. These organisms may include species considered as pests and pathogens. An example of this occurred in North American where 25 new Phytophthora species, have been unintentionally but extensively introduced into restoration sites by planting out infected plants from nurseries.

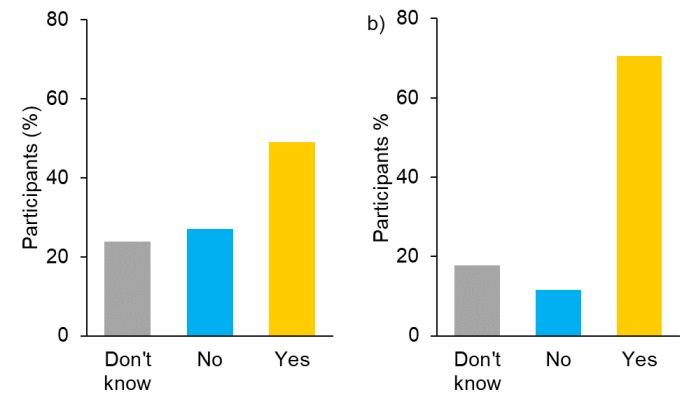

The survey distinguished between Risk Assessments (defined as an assessment made before an activity is carried out to identify and assess the potential impacts and risks of that activity) and biosecurity guidance/best practice (actions or procedures on the ground that should limit the risks of plant pests and pathogens spreading). The results highlight several potentially serious short-comings with respect to risk assessments and biosecurity protocols (Figure 2). Firstly, the majority of participants either didn’t have or didn’t know if they had a risk assessment for plant pest and pathogens (51%). While over 70% of participants did have biosecurity best practice guidance in place that might be expected to reduce the risks of pests/pathogens establishing; if a risk assessment has not been carried out first then it is not clear that the biosecurity protocols in place were appropriate for the risks. Secondly, nearly a quarter of participants didn’t check if the biosecurity protocols were followed. Thirdly most of them didn’t know or didn’t have someone responsible for biosecurity in their organisation. Filling these three gaps would be a quick win in terms of improving biosecurity in the habitat creation/restoration.

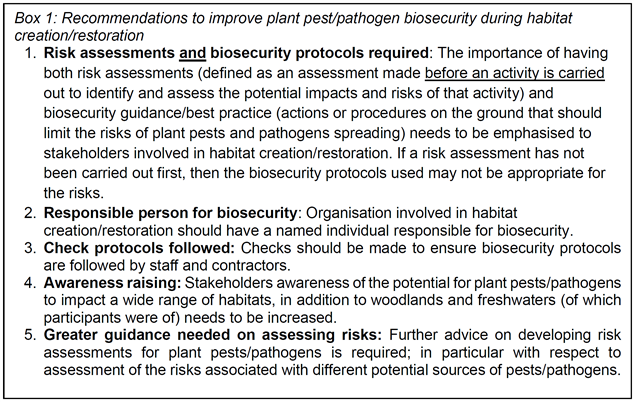

The results from the survey were used to produce five recommendations with respect to plant pests/pathogens and habitat creation/restoration (Box 1).

We would like to thank all those from CJS that participated in the survey, your input was really appreciated and allowed us to get a far larger number of responses than we had hoped for. Thank you for your time.

Further information about this project please contact Ruth.Mitchell@hutton.ac.uk

Further information about Scotland’s Plant Health Centre is available at https://www.planthealthcentre.scot/

and about NatureScot at https://www.nature.scot

Updated information October 2023:

This survey was undertaken as part of a Fellowship on Plant Health and the Natural Environment, funded by Scotland’s Plant Health Centre in collaboration with NatureScot. The Fellowship also investigated which plant pests could threaten Scottish moorlands and explored key principles to underpin the assessment and reduction of plant pest risks to the natural environment. The full report and policy summary from the fellowship are available on the Plant Health Centre website.

Recommendations include: (i) emphasising to stakeholders involved in habitat creation/restoration the importance of having both plant health risk assessments and biosecurity guidance/best practice protocols in place, and ensuring there is a named individual responsible for biosecurity; (ii) improvements to the UK Plant Health Risk Register (PHRR) to better include the impact of plant pest/pathogens on the natural environment; (iii) using the pest lists collated as part of the fellowship as an awareness raising exercise to highlight the risks to other non-woodland habitats and (iv) clarifying roles and responsibilities for plant health in the natural environment and creating a standard operating procedure for identification of, and response to, plant pests in the environment.

The fellowship also led to the creation of a Biosecurity Best Practice for Conservation guidance document.

More from James Hutton Institute